On January 1st, 1983, we discovered a portal to an empty void. As we poked and prodded it, we realised that we could shape this void however we liked. So we began to construct a world that mirrored our collective dreams built entirely from logical structures.

It was hard work creating the infrastructure and deciding how everything should fit together; we didn’t know any of the answers - we were exploring uncharted territory.

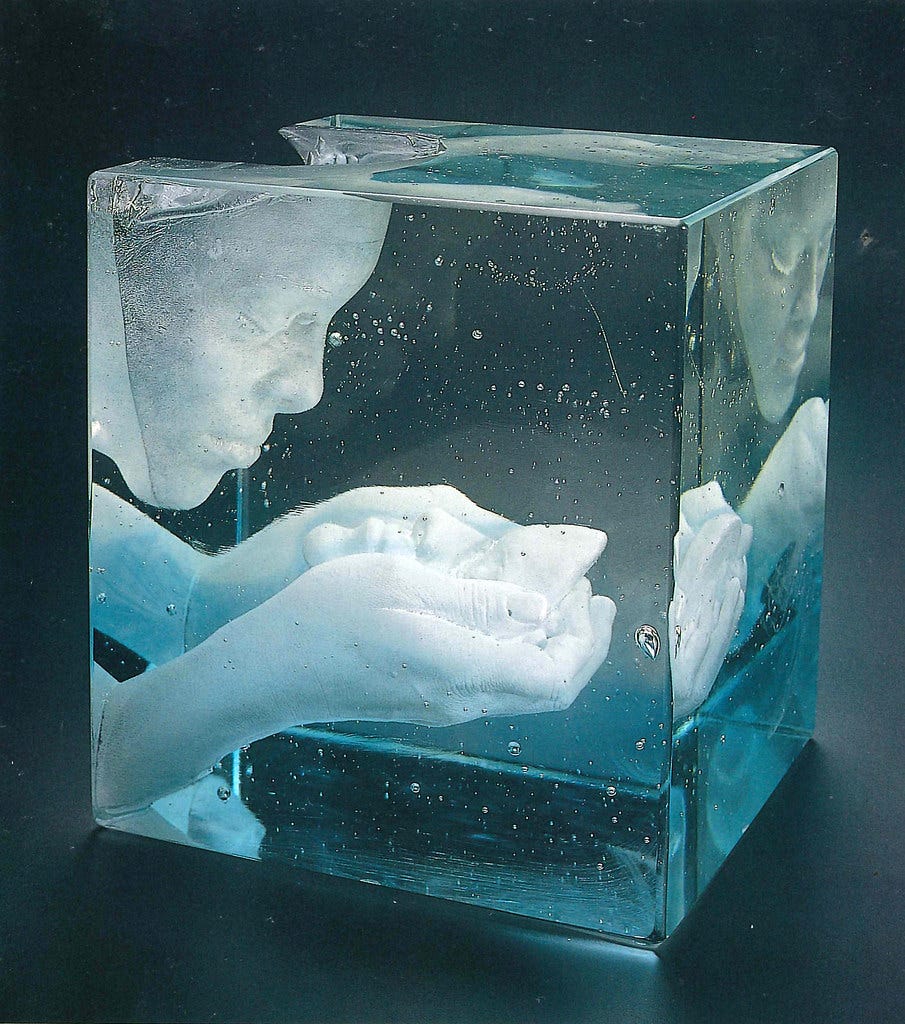

We couldn’t go to this place; we could merely peek behind the veil through simplified interfaces we created. Over time those interfaces have become more complicated and given us a more transparent window into the world we’re constructing.

The early settlers began creating shared spaces for people with similar interests or values. Everything felt a bit whacky and all over the place, without a consistent set of standards, but the places were oriented around the needs of that community; they felt pretty intimate.

It was a lot of work maintaining the infrastructure; people had a life to lead on earth, and often development was slow. As a result, things would crack at the seams and often collapse entirely.

Over time companies developed ubiquitous platforms; these places gave everyone a sense of safety and security. No matter which community you engaged with, they all had a familiar interface for interaction. They grew so large that most of your social network would all be in one place.

These places were free to visit; they encouraged you to express yourself and put more of your life into the spaces. Then, to pay for upkeep and development, they began collecting all of the data they could about you and using it to serve targeted advertisements. So as you walked down the streets, you’d see billboards specialised just for you.

The platforms began profiting immensely from the content you and the rest of the communities provided for them. You didn’t need to pay for the service, but the manipulation led you to spend more money and time than it would have cost if you had just paid for the service in the first place.

The creators of the platforms began to grow in power; they were like a monarchy of the digital world. Their influence was able to shift the perceptions of the community members and influence the physical world as well.

Since they profit off your engagement with the platform, they began altering the shape of the space and mediating the content shared with you to maximise profits.

Large numbers of people began becoming concerned about the impacts these spaces were having on society. They wanted to leave and find a new place to spend their time; but, it was hard to go anywhere else. Everyone you knew was on the platforms; if you left, you’d be exiled from those communities.

Small groups began going back to their roots and trying to reclaim control over the spaces they inhabited. They wanted to create spaces that better aligned with the needs of the groups using them rather than the needs of a corporation. They wanted to truly own their own digital identities and the content that they had created.

They started to deconstruct the communication and interaction patterns that people used across digital platforms to create bridging protocols between spaces to allow them to be more interconnected.

They worked on tools that allowed everyone to create safe and secure environments to inhabit; they reduced the friction involved in creating them.

To increase the security and longevity of the platforms, they were upheld on a decentralised network. So everyone carried a little bit of the load; it was similar to an electricity tax rather than paying with data and manipulation.

Individual communities could subsidise this by allowing organisations to host parts of their infrastructure in exchange for data or money.

As we built more of the infrastructure, we noticed all of the issues that can arise through interoperable and decentralised spaces. The old power structures began to erode, and they were replaced with new ones. The platforms that were the most successful were still the ones that captured the most of our attention or were the most exploitative. We had delegated control from people into hulking systems; there was tyranny without a tyrant.

This time around, though, we had no way to keep anyone accountable or to regulate the spaces; there was a downward push on wages, and it wasn’t easy to maintain order in society. Private dens popped up, which supported all kinds of unscrupulous behaviour.

Society became this incredibly tangled web of complexity, and it was increasingly difficult to navigate.

People perceived reality through endless lenses overlaying one another; time and space were being distorted in incomprehensible ways.

We’ve only just begun our journey, but I have hope that we can build towards a better future, one which is healthier for individuals and societies.

Things don’t seem as clear cut as I once thought they were. Every decision we make in one direction has a bunch of side effects. For example, privacy and decentralisation may cost usability, understanding, security or safety. In which situations should we make which trade-offs?

I don’t know where this will all lead to, but I know one thing for certain. We need people pushing towards a brighter future, or we’ll end up somewhere that we don’t want to be.